Table of Contents

Introduction

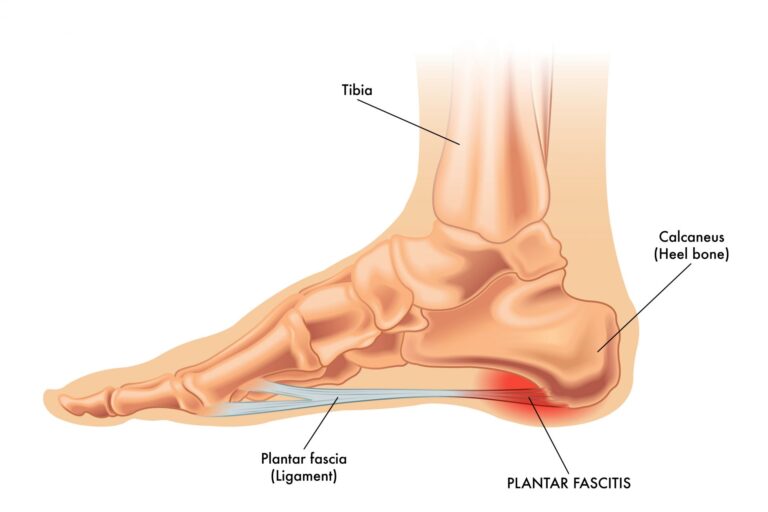

The most recognised term for this condition is plantar fasciitis (plan-tur fash-e-i-tis). More modern names for this condition are plantar heel pain or plantar fasciopathy. These terms are now more commonly used in research circles due to our updated understanding of this condition. However, as plantar fasciitis is the most recognised term by both patients and most healthcare professionals, we tend to use it.

This condition used to be thought to be caused by local inflammation of the plantar fascia, a long tough band of connective tissue on the sole of your foot. This tissue starts at the heel and ends at the balls of your feet. We now know the cause of plantar fasciitis is more complex than originally thought and is now seen on a spectrum that includes both inflammation and degenerative changes.

Background of Plantar Fasciitis

This condition is quite a common one which most people have at least heard of. The most common group of people who experience plantar fasciitis is middle-aged and older aged, and generally more sedentary. In contrast, this heel pain is also seen frequently in runners. Those who have a high BMI (body mass index), increased training loads or activity too quickly, or spend long periods on their feet for work are most commonly at risk of plantar fasciitis.

What are the most common signs and symptoms?

Those who have this condition commonly report similar signs and symptoms which raises the suspicion of plantar fasciitis. The most common include:

- Pain localised at the bottom of the heel, usually more on the inside at it’s attachment (medial calcaneal tubercle),

- Pain when you take your first steps after waking up in the morning, which typically reduces or clears quickly.

- Pain is worse with weight-bearing activity, especially after periods of rest.

- Symptoms can be described as sharp during the height of pain, and also a general dull ache.

Do I need imaging such as MRI or ultrasound scan to diagnose this?

The simplest answer here is no. A clinical exam is usually enough to diagnose this condition. If we decide to refer you to diagnostic imaging, it can be to confirm a diagnosis or rule out other reasons why you might have plantar heel pain. Not all heel pain is caused by the plantar fascia, and this is why a thorough assessment from your physiotherapist or other healthcare professional is important. Other structures such as tendons and local peripheral nerves, or other reasons such as inflammatory conditions and referred spinal nerve root pain are differential diagnoses that can mimic/masquerade as plantar fasciitis. Bone injuries such as stress fractures can also cause similar symptoms.

Although plantar fasciitis is a more common cause of heel pain, a thorough discussion and physical exam from a physiotherapist or other health care professional is essential.

So what can be done to treat this?

There are many different treatment/management strategies utilised by many different types of healthcare professionals. Some are supported by evidence, and many are not. A lot of treatments are anecdotal or outdated with new research and information. Some treatments are even advised against but still found in clinical practice.

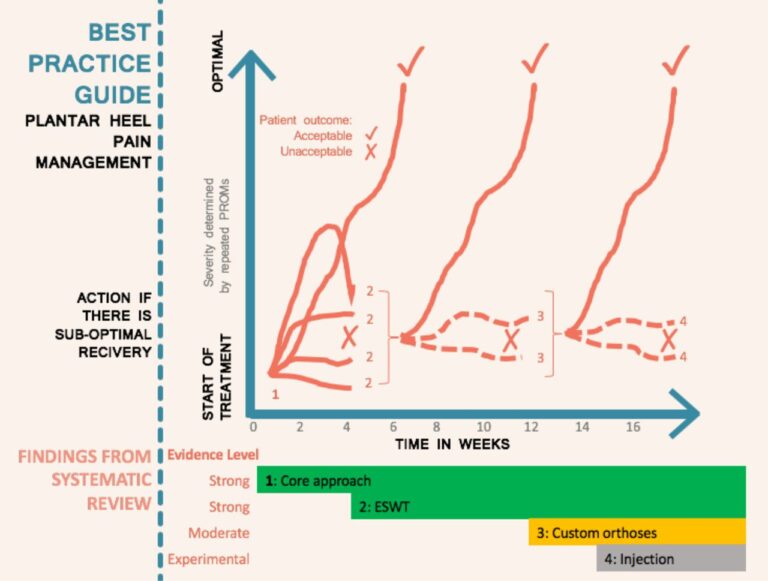

The current clinical practice for best practice was outlined in a study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine (BJSM), and the paper can be found here! The authors brought together randomised control trials, clinical reasoning from clinician-researchers, and the patient voice, to develop best practice guidelines for the clinical management of plantar heel pain.

Core Approach

Current evidence suggests an initial core approach which should be foundational to every patient seen this plantar fasciitis. The three core components are education, stretching, and taping.

Education: the key to prevent recurrence. In order to treat the pain, we must understand why it was there in the first place. The education given to you should be specific to you and your presentation. This should not just be a standardised speech with no individualisation. Topics of education should include a focus on your key pain drivers, physical and non-physical factors, load management, footwear, and other areas that are appropriate for you.

Stretching: this is an easy and effective way to help mobilise the painful tissue. As this strategy is non-impact and very controlled, this should be utilised in your rehabilitation. With plantar fasciitis, it is common for people to want to rest and offload. However, we know that keeping the area mobile and stretching little and often can be very effective. Stretching should be done for the connective tissue at the sole of the foot and the calf muscles. Often you will also be given resistance or endurance-based exercises for the muscles local to your plantar fascia to help support the arch of the foot and allow the lower leg to be more efficient with loading. Examples of stretches can be found here.

Taping: the type of taping utilised in research is low-dye tape. This is more commonly known in the UK as zinc oxide tape. This tape is very useful as it can be applied to offload the plantar fascia and provide support to the arch of your foot. Taping is a cost-effective modality which should be used to keep people active and reduce pain. Other styles of type such as K-tape are commonly used in this condition. However, this type is designed to stretch with your body and will apply no offload or physiological benefit. The gold standard zinc oxide tape can be found here.

Stepped Approach

It was recommended by the authors of the best practice guidelines to wait 4-6 weeks before starting additional treatments. This was mostly due to the cost and availability of treatment. In private practice, it is beneficial to combine some of the stepped approaches earlier given their benefit and accessibility for private medical insurance and self-funding patients.

Shockwave Therapy (ESWT): this is a great treatment for plantar fasciitis. This treatment has the best evidence of any adjunctive treatment and seen as far superior to treatments such as massage and acupuncture. ESWT has positive short, medium, and long-term benefits on pain and quality of life. If access allows, ESWT is a great treatment to use from the beginning.

Click here to see my blog post on the benefits of shockwave therapy.

Orthotics: custom orthotics (insoles) was found to have strong efficacy in the short term for pain. These are used to unload the plantar fascia, and can be a longer term option instead of using zinc oxide tape. Over the counter insoles can also be considered to help offload the sole of the foot, but custom orthotics allow very specific and tailored help for your foot.

Injections: this can be with medications such as steroid to help reduce inflammation, or PRP (platelet rich plasma) to help stimulate healing. These options are often only done if symptoms have been resistant to prior treatment. The most common injection using steroid and local anaesthetic, deposited in the surround area of the plantar fascia origin.

The image above shows the management approach for plantar heel pain when a person progressively fails to recover with the addition of extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) at 4 weeks if the core approach is not working and then the addition of orthoses at 12 weeks if there is still a suboptimal improvement. PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

Physiotherapists are often perfectly placed to diagnose this condition, and more importantly in a place to treat plantar fasciitis. Physiotherapy is first line for plantar fasciitis management, and is very successful in guiding those struggling with pain through their recovery,

Bradley Rugg see’s this condition often in his clinic. He can perform any of the listed interventions from taping and shockwave therapy, all the way up to steroid injections. Bradley also has the qualification to refer for diagnostic imaging such as MRI and ultrasound scans, and can refer to consultant doctors for 2nd opinions or treatment if necessary.